During a City Council hearing on Friday, a controversial Boston police intelligence gathering centre was heavily criticised and repeatedly questioned about possible civil rights violations and racial profiling. However, department leaders defended the operation as an important tool that helps keep communities safe.

The city is about to get $3.4 million in government grants for the Boston Regional Intelligence Centre, a “fusion centre” that keeps track of, among other things, the city’s gang database or a list of people who might be in a gang.

The BRIC centre could hire eight more analysts with the help of four funds. This would help the centre fight gang-related crime and terrorism and be better prepared for emergencies.

But the City Council has to agree for the city to take the grants, and it hasn’t done so because councillors want to talk about police change in more depth. In fact, some of the grants that were being looked at on Friday were left over from as far back as 2020.

In particular, councillors and civil rights groups have been asking for more information about BRIC’s gang database for years. They want to find out why so many Black and Latinx city residents have been on its rolls in the past. Some reformers who want to make things better have called for it to be taken down.

During Friday’s hearing, the tough questions kept coming.

Councillor Ruthzee Louijeune asked, “Where are we in terms of trust?” She pointed out that problems with the way BRIC works have been shown in court cases outside of the city.

For example, a court decision from last year criticised BRIC’s gang database for “its reliance on an erratic point system built on unsubstantiated inferences.”

In that case, a group of federal judges sided with a Salvadoran man who said that police made a mistake when they said he was a member of the MS-13 gang.The judges found problems with how the gang database was put together, which was a big part of the decision. The court found that “the list of ‘items or activities’ that could lead to’verification for entry into the Gang Assessment Database’ was shockingly wide-ranging.”

“Many of us don’t think BRIC is working for the best interests of Black and brown people, Muslims, and people with different backgrounds,” said Councillor Julia Mejia on Friday. “We don’t have that information that makes us think you have our best interests in mind,” they said.

Some city councillors and people who work for the police supported BRIC. Ed Flynn, the president of the Council, said that BRIC does “very important work” that helps stop “heinous crimes.” The meeting was led by Councillor Michael Flaherty. He said that BRIC helps solve homicides in Boston.

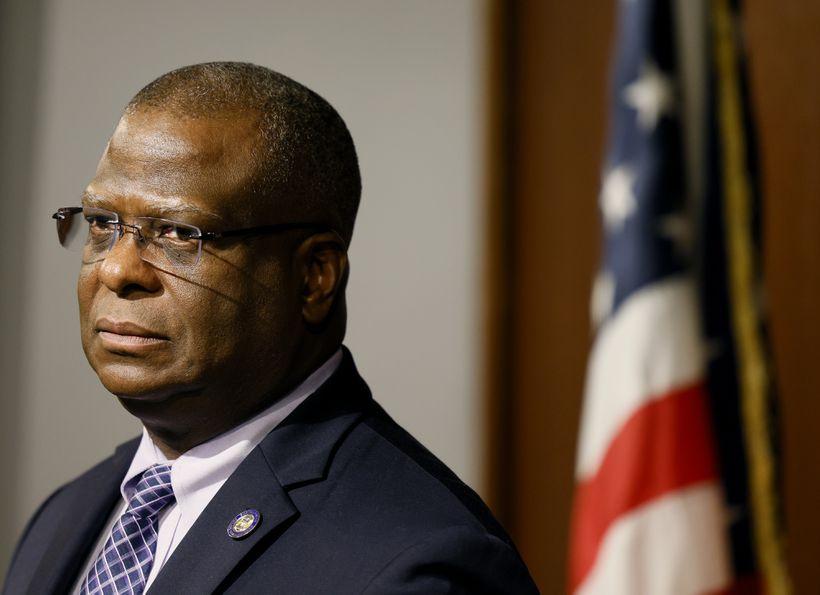

Michael Cox, the head of the Boston Police Department, said that BRIC’s job is not about making people of colour look bad.

Cox said, “It’s mostly about figuring out who is behind the violent crime in our city and keeping track of that information.”

At Friday’s hearing, city officials stressed that BRIC stays in line with the city’s Trust Act, which says that Boston cops can’t help with deportation cases. In the past, the police force has been asked about how much it works with immigration authorities.

BPD says that BRIC looks at different police records and information to decide if a person meets the requirements to be in its gang database. The centre can still decide not to add people to the database even if they meet the 10-point requirement but are not involved in gang-related crime.

Alex Marthews, the head of the civil liberties group Digital Fourth, said that BRIC’s “mission creep” meant that it was spying on protests and activists in the wrong way and letting “data-fueled harassment of young Bostonians of colour” happen.

He said, “BRIC is a hammer looking for a nail.”

Fatema Ahmad, who lives in Dorchester and is the head of the Muslim Justice League, said that the BRIC operation gathers too much information and is not clear.

She said, “This has hurt people.” “Real people get hurt by it.”

Kade Crockford, who runs the Technology for Liberty programme at the American Civil Liberties Union in Massachusetts, said that BRIC can collect and share information about someone without ever having a criminal reason.

During the meeting, Crockford said via Zoom, “That is very scary.” “The Boston Police Department’s job is to look into crimes, not what people say or think about politics.”

As soon as Wednesday, the council could vote on the different BRIC funds.