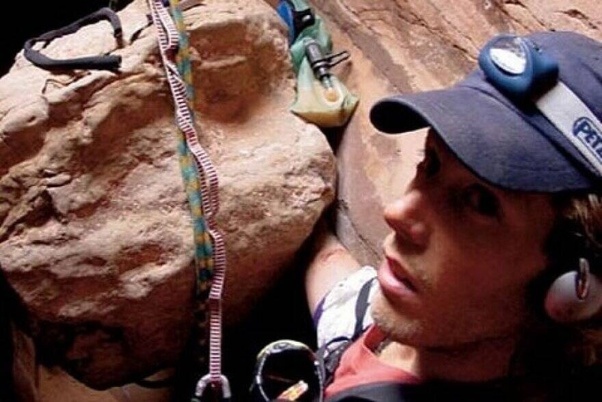

Mountaineer Aron Ralston spent 127 hours pinned by a boulder in Utah’s Bluejohn Canyon — until he amputated his own arm and escaped.

In April 2003, Aron Ralston was on a solo climbing trip in Utah’s Canyonlands National Park when an 800-pound boulder suddenly fell from above him. The next thing he knew, his right arm was lodged between the boulder and a canyon wall. Quite literally caught between a rock and a hard place, Ralston was also trapped 100 feet below the desert surface and 20 miles away from the road.

Though he had enough provisions to get him through a few days, Aron Ralston was forced to drink his own urine after he ran out of food. Convinced that he was going to die, he recorded goodbye messages to his loved ones on his video camera. He even carved his own epitaph into the canyon wall so that people would know when he passed away.

But then, Ralston fell asleep and had a dream in which he saw himself with one arm. So after he woke up, he broke his own arm and amputated it using a cheap, two-inch knife — in a grueling process that took an hour.

He was ultimately able to free himself and make it to safety in a harrowing ordeal that inspired the 2010 film 127 Hours.

After seeing 127 Hours, Aron Ralston called it “so factually accurate it is as close to a documentary as you can get and still be a drama.”

Starring James Franco as Ralston, 127 Hours caused several viewers to pass out when they saw Franco’s character amputating his own arm. Some viewers were even more horrified when they realized that 127 Hours was actually a true story.

Before his infamous 2003 canyoneering accident, Aron Ralston was just an ordinary young man with a passion for rock climbing. Born on Oct. 27, 1975, Ralston grew up in Ohio before his family moved to Colorado in 1987.

Years later, he attended Carnegie Mellon University, where he studied mechanical engineering, French, and piano. He then moved to the Southwest to work as an engineer. But five years in, he decided that the corporate world wasn’t for him and quit his job to devote more time to mountaineering. He wanted to climb Denali, the highest peak in North America.

In 2002, Aron Ralston moved to Aspen, Colorado, to climb full-time. His goal, as preparation for Denali, was to climb all of Colorado’s “fourteeners,” or mountains at least 14,000 feet tall, of which there are 59. He wanted to do them solo and in the winter — a feat that had never been recorded before.

In February 2003, while backcountry skiing on Resolution Peak in central Colorado with two friends, Ralston was caught in an avalanche. Buried up to his neck in snow, one friend dug him out, and together they rescued the third friend. “It was horrible. It should have killed us,” Ralston later said.

No one was seriously hurt, but the incident perhaps should have triggered some self-reflection: A severe avalanche warning had been issued that day, and if Ralston and his friends had seen that before climbing the mountain, they could have avoided the dangerous situation altogether.

But while most climbers might have then taken steps to be more careful, Ralston did the opposite. He kept climbing and exploring hazardous terrains — and oftentimes he was completely on his own.

Just a few months after the avalanche, Aron Ralston traveled to southeastern Utah to explore Canyonlands National Park on April 25, 2003. He slept in his truck that night, and at 9:15 a.m. the next morning — a beautiful, sunny Saturday — he rode his bicycle 15 miles to Bluejohn Canyon, an 11-mile-long gorge that in some places measures just three feet wide.

The 27-year-old locked his bike and walked toward the canyon’s opening.

At around 2:45 p.m., as he descended into the canyon, a giant rock above him slipped. The next thing he knew, his right arm was lodged between an 800-pound boulder and a canyon wall. Ralston was also trapped 100 feet below the desert surface and 20 miles away from the nearest paved road.

To make matters worse, he hadn’t told anyone about his climbing plans, and he didn’t have any way to signal for help. He inventoried his provisions: two burritos, some candy bar crumbs, and a bottle of water.

Ralston futilely tried chipping away at the boulder. Eventually, he ran out of water and was forced to drink his own urine.

Early on, he considered cutting off his arm. He experimented with tourniquets and made superficial cuts to test his knives’ sharpness. But he didn’t know how he’d saw through his bone with his cheap multi-tool — the kind you’d get for free “if you bought a $15 flashlight,” he later said.

Distraught and delirious, Aron Ralston resigned himself to his fate. He used his dull tools to carve his name into the canyon wall, along with his birth date, his presumed date of death, and the letters RIP. Then, he used a video camera to tape goodbyes to his family and tried to sleep.