The “keto” diet, which consists of eating a lot of fat and little to no carbohydrates, has been gaining popularity. A “keto-like” diet, according to a recent study that was presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session Along With the World Congress of Cardiology, may be linked to higher blood levels of “bad” cholesterol and a doubled-up risk of cardiovascular events like angina, blocked arteries that require stenting, heart attacks, and strokes. The body uses carbohydrates as its primary source of fuel to power daily activities.

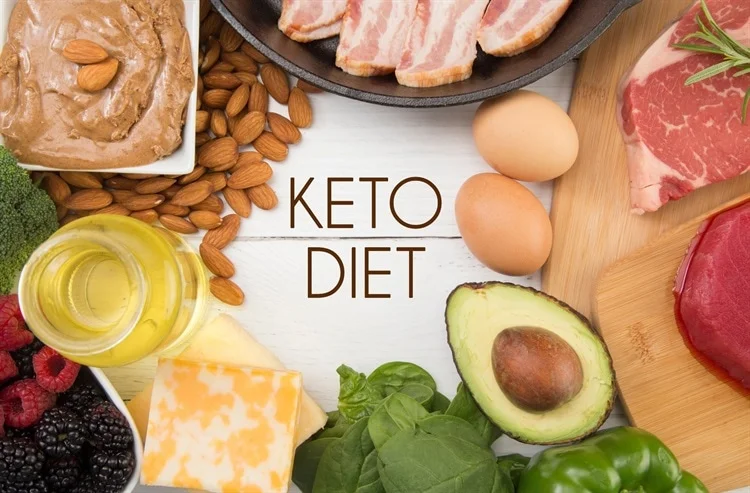

In low-carbohydrate, high-fat (LCHF) diets, such as the ketogenic diet, carbohydrates (such as those found in bread, pasta, rice, and other grains, as well as in baked goods, potato products like fries and chips, and high-carbohydrate fruits and vegetables) are limited.

The term “ketogenic,” or “ketone generating,” refers to a diet that produces ketones, which the body uses as fuel when there are no carbs present. In general, proponents of a ketogenic diet advise keeping protein to 20% to 30% of total daily calories, carbs to 10% of total calories, and getting 60% to 80% of daily calories from fat.

An LCHF diet can cause higher levels of LDL cholesterol in some people, according to some earlier research. The effects of an LCHF diet on risk for heart disease and stroke have not been thoroughly researched, according to Iatan, even though high LDL cholesterol is an established risk factor for heart disease (produced by atherosclerosis, a buildup of cholesterol in the coronary arteries).

Iatan and her coworkers classified an LCHF diet for this study as having more than 45% of total daily calories from fat and no more than 25% of total daily energy or calories from carbohydrates. This diet was referred to as “keto-like” and “LCHF” because it contains less calories from fat and more carbohydrates than a rigorous ketogenic diet. Those who didn’t fit these requirements and had more wholesome eating routines were characterized as having a “standard diet.”

The research team examined information from the UK Biobank, a sizable prospective database with health data on more than 500,000 UK residents who were tracked for at least ten years. 70,684 participants completed a one-time self-reported 24-hour diet after joining the biobank.